Description

- Conodonts

- Mississippian Age

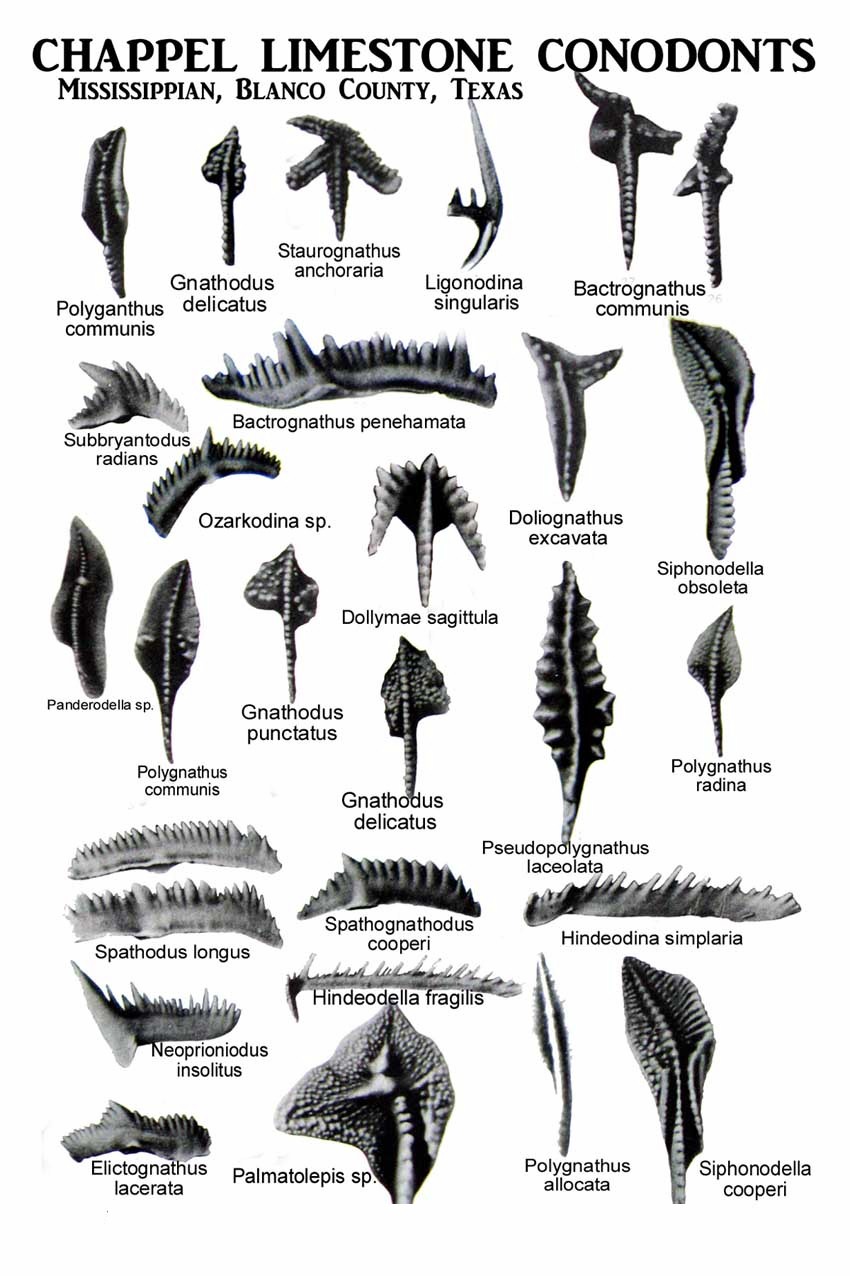

- This collection consists of 36 different conodont genera from the Lower Mississippian Age of Texas. The collection highlights many of the different morphologies seen in the group during its existence. The majority of specimens are complete and show excellent preservation.

- Each of the microscopic specimens comes in a 1.25″ clear display jar with and ID Label as shown. (See Photos for ID’s) The entire collection will come in the 8″ x 13″ Display as shown.

Conodonts are minute toothlike fossil composed of the mineral apatite (calcium phosphate); conodonts are among the most frequently occurring fossils in marine sedimentary rocks of Paleozoic age. Between 0.2 mm (0.008 inch) and 6 mm in length, they are known as microfossils and come from rocks ranging in age from the Cambrian Period to the end of the Triassic Period. They are thus the remains of animals that lived during the interval of time from 542 million to 200 million years ago and that are believed to have been small marine invertebrates living in the open oceans and coastal waters throughout the tropical and temperate realms. Only recently has the conodont-bearing animal been found, preserved in fine-grained rock from North America. Conodont shapes are commonly described as either simple cones (like sharp teeth), bar types (a thin bent shaft with needlelike cusps or fangs along one edge), blade types (flattened rows of cones of ranging size), or platform types (like blades, with broad flanges on each side making a small ledge or platform around the blade). Well over 1,000 different species or shapes of conodonts are now known.

Some conodonts exist in two forms, “right” and “left.” They are known to have occurred in bilaterally symmetrical pair assemblages in the animal, like teeth but more delicate and fragile. The few assemblages discovered so far appear to contain as many as nine different species, or forms, of conodonts. Bars, blades, and platforms may all be present in a single assemblage or apparatus. How single cones fitted into assemblages is uncertain. The conodont apparatus seems to have been placed at the entrance to the gut and to have assisted in food-particle movement. The relationship of this little animal (30–40 mm long) to the known wormlike animal groups is still debatable, and no exactly compatible creature is known to exist today.

Conodonts are very useful fossils in the identification and correlation of strata, as they evolved rapidly, changing many details of their shapes as geologic time passed. Each successive group of strata thus may be characterized by distinctive conodont assemblages or faunas. Moreover, conodonts are very widespread, and identical or similar species occur in many parts of the world. Black shales and limestones are especially rich in conodonts, but other sedimentary rock types may also be productive. In some parts of the world assemblages of conodonts, regarded as those of animals living out in the open ocean, can be distinguished from others thought to belong to inshore communities.

The oldest conodonts are from Lower Cambrian rocks; they are largely single cones. Compound types appeared in the Ordovician Period, and by Silurian time there were many different species of cones, bars, and blade types. The greatest abundance and diversity of conodont shape was in the Devonian Period, wherein more than 50 species and subspecies of the conodont Palmatolepis are known to have existed. Other platform types were also common. After this time they began to decline in variety and abundance. By Permian time the conodont animals had almost died out, but they made something of a recovery in the Triassic. By the end of that period they became extinct.

Conodonts are most commonly obtained by dissolving the limestones in which they occur in 15 percent acetic acid. In this acid they are insoluble and are collected in the residue, which is then washed, dried, and put into a heavy liquid such as bromoform through which the conodonts sink (the common acid-insoluble mineral grains float). The conodonts are studied under high magnification by using a binocular microscope. Work on these fossils is now carried out in many countries. Originally discovered in Russia in the middle of the 19th century, they were recognized as being very useful in rock dating and correlation in the United States and Germany about 100 years later. Perhaps the most detailed correlations by means of these microfaunas have been made in the Devonian System of rocks. Thick continuous sequences of limestones in which they occur have been especially studied in North America, Europe, and Morocco, and the succession of conodonts there serve as reference standards. The conodonts obtained from similar rocks elsewhere can then be compared with these, and correlations can be made. Strata distinguished by special conodont assemblages are termed zones. There are 10 generally recognized conodont zones in the Ordovician, 12 zones in the Silurian, 30 in the Devonian, 12 in the Carboniferous, 8 in the Permian, and 22 in the Triassic. Refinements and variations of these zonal schemes are made from time to time as knowledge increases.

The extinction of the conodont animal remains an unsolved mystery. It does not seem to have coincided with a particular geologic event, nor were there extinctions of other groups of marine creatures at the same time. Records of conodonts from younger strata have all proved to be of fossils derived from older rocks and reburied at the later date.